CURATOR'S CHOICE SM

Exhibition Reviews

| Home | | Museum

Guide | | International |

| Theater |

Julia Slaff

"America is Hard to See," Julia Slaff concludes her three-part

examination of the opening exhibit of the "new" Whitney Museum,

The Whitney Museum continues “America is Hard To See” on the sixth, fifth and third floors. Exploring the layers of American art from the 1950s to the present day, the exhibit continues to try and solve the mystery of American art’s parameters. This is the final chapter of my three part report on this historic overview of American art, which is opener for the museum’s new location in the trendy West Village. As I explained in earlier installments of the series, the floors are subset into thematic “chapters” in the building. Because of the diversity apparent in the American art scene, each chapter is named for a work within it over any particular style or movement. Floor Six

Following World War II, Artists responded to the new era with different visual vocabulary and materials. Hard-edge abstraction and dynamic pop art replaced the styles of cluttered abstraction with expressionism. Modern technology fostered the development of these artistic practices. Artists experimented with new media, providing even more innovative works during the 1960s and 1970s. The chapter “White Target” follows the time after 1950s Abstract Expressionism. Artists abandoned chaos for showy brushwork and simplicity. Frank Stella pointed out in 1964 that the only solution for painters to seek artistic innovations was to escape the complicated world of Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism. Large canvases with thick white-impasto passages, with green or black accents, are common features of “White Target” paintings. Dismantling forms to their essentials was the goal of these post-abstract expressionists. Their process turned away from traditional compositional rules, yet maintained a balance of colors, textures and shapes. Stella also noted that these new artists strove to get that “thing in the middle, and symmetrical.” He explained that “the balance factor isn’t important. We’re not trying to jockey around.” Stella was implying that the painting focus became the geometry and physicality of a work, including the canvas itself.

Many of the paintings in this chapter are divided down or across the middle of the canvas, like John McLaughlin’s “#1” from 1963. Paintings like Jasper Johns’ “White Target,” the chapter’s namesake, have a central focal point. Changing the relative position of an image, instead of “jockeying” its parts, was Johns’ and his peers’ process. In opposition to the Abstract Expressionists, the paintings in “White Target” have paint applied in a flat manner. The canvases consequently evoke bold yet reserved emotion. Painters and sculptors within this chapter changed the conversation of artistic expression to allow for innovative and daring pathways. The chapter “Scotch Tape” is named for a Jack Smith film. The film is named for an accident that occurred during its production, when a piece of cellophane tape invaded the camera’s lens. Smith, by titling the film after this slip, inadvertently made it important, implying “the real world’s intrusion into art” as the Whitney eloquently writes.

Artists in this chapter assembled untraditional materials found in thrift shops and along city streets. They took a collage approach to art making, piecing together deconstructed furniture, assembling burnt paper bits, comics, conveyor belts, and even a stuffed pheasant. Paintings are assembled with found objects. Following World War II, mass-production and consequential overproduction led to an increase of “junk.” Along with impending tensions of Cold War, artists turned to what they knew best in an attempt to resist Cold War consumption that plagued the American consumer. The battle is seen in different works in the chapter through irony, humor, creative intensity and material transformation. Vibrant colors and animated compositions are common in the works from the “Large Trademark” section on the sixth floor. Paintings and sculptures in this chapter date back to the 1960s, an era when Abstract Expressionism morphed for the commercial realm with the advent of Pop art. With color television’s increased popularity, selling to an American consumer became an important part of the culture - and especially to those who made it. Pop artists were inspired by the images of packaging, advertisements, newspaper photography and comic books. Many leading Pop artists such as Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, Ed Ruscha commenced their careers in commercial art. Warhol was an illustrator and Rosenquist was a billboard painter. Ruscha trained as a graphic designer. These artists produced works with flat, graphic, and mechanically-appearing paintings, occasionally rendered using printing and photographic methods, a force of habit from their commercial backgrounds.

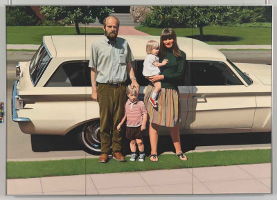

“Large Trademark” presents these artists’ feelings towards consumer culture’s milieu. Works like Wayne Thiebaud’s frosted cakes evoke more cheer and celebration. Others are subtly critical of this new version of the American dream, plagued by over-consumption and social issues of race and class. Robert Bechtle’s painting “‘61 Pontiac” depicts an ordinary American family posed in front of their new automobile. Upon close observation, one will notice that the new coup is much more detailed than the family’s faces. “Madonna and Child,” Allan D’Arcangelo’s portrait of Jackie and Caroline Kennedy, renders the First Mother and Daughter in a virginal and holy manner. The saturated hues and cartoonish depiction of the figures evokes their materialistic associations. Their public importance, and materialism they wear, together portray a royal yet demeaning picture of these public figures. Despite its visual joy, the tone of the Pop Art movement was frequently impassive and frigid. The Whitney cites, in “Large Trademark,” that Pop Art was responsible for a media sensation for its “charges of vulgarity” that are still felt as aftershocks in American Culture.

Any cheer from the “Large Trademark” gallery fades when venturing into the “Raw War” chapter. During the later 1960s and into the 1970s, the United States underwent great social and cultural change, particularly with rights for women, racial minorities, and others left behind. Artists addressed these issues through their art as they had done in the 1930s, as an outcry for necessary social change. There is an uneasiness, and almost unnaturalness, filling the “Raw War” chapter. The walls are full of a variety of works ranging from noir-esque photographs to harsh-hued satirical advertisements, and even sculptural multimedia pieces. There is a clear message for a need for change. Intense photographs of the Civil Rights movement are displayed by photographers Danny Lyon and Gordon Parks. A fake public service announcement by Milton Glaser titled “Don’t Eat Grapes” comments on the plight of exploited farm workers. Numerous pieces address the issue of American “intervention” in Vietnam, particularly a Howard Lester film displayed in a corner. “One Week” (1970) flashes black and white photographs of young handsome soldiers beside a rising death tole, set to twangy all-American folk music. An apparent paradox of pride and disappointment makes the “Raw War” chapter empowering for Baby Boomers - but potentially uncomfortable for those of the Greatest Generation. “Rational Irrationalism” explores how artists in the 1960s broadened their media horizons by delving into more industrial processes. New materials became available to artists such as neon, latex, lead, resin, and plexiglass. As the Whitney notes, “the factory became a studio and the hardware store a source of art supplies.” This phenomenon formed artists known as Minimalists. Artists such as Donald Judd and Robert Smithson were active in the movement and explored simple geometric shapes with new media and techniques. Judd’s 1966 “Untitled,” and Smithson’s “Alogon,” are the results of these new processes. Their intentions were to stimulate a viewer’s attention to the “complexities of perceptual experience” of their body, the piece and their present environment. Some artists investigated these art inquiries by forming canvases to play with the relationship between the actual physical experience and spatial illusionism, as Al Loving’s Rational Irrationalism does.

Several artists spiraled away from stiff geometric shapes, finding ways to use these materials with spontaneity. It was similar to Jackson Pollock’s full-bodied art-making process but with industrial methods. The goal was to make art into a more “active process” yielding to external influences such as gravity or the artists’s body. Eva Hesse’s “No Title” exemplifies the sporadic nature of this artistic spin off and also toys with the link between a viewers physical and illusionistic experiences. The Whitney held an exhibition in 1969 which displayed artists from this chapter. The show, titled “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials” included artists such as Hesse, and Rafael Ferrer, Richard Serra, and Keith Sonnier. The sixth floor terrace continues this ’69 exhibition with videos of the performance program which showed the relationship between contemporary music, dance, and visual art.

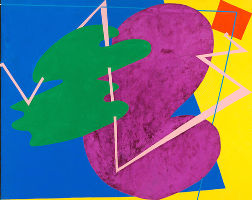

Fifth Floor “Threat and Sanctuary” marks a time in contemporary art when painting was not the standard. In the late ‘60s, Minimalists and Post-Minimalists saw the medium as archaic. Contemporary art’s emphasis on language and photography was almost the nail in paintings’ coffin. Its lessened popularity made way for reinvention of paint application and what the Whitney describes as “critical taboos like figuration and bad taste.” This chapter displays exemplary examples of this painting experimentation. Painters such as Jack Whitten and Robert Reed painted in a sculptural manner, pouring and spreading the medium across canvases. Elizabeth Murray’s “Children Meeting” experiments with expressive and geometric shapes and high-contrast colors, creating a chaotic but balanced composition. “Cabal,” a Philip Guston painting, engages with the figure; this was a leap from the artist’s formative Abstract Expressionist years working with animated forms. The experimental freedom stimulated works like Cy Twombly’s “Untitled” and encouraged symbolism and humor such as Chuck Close’s “Phil” revamping a medium near extinction.

Artists began employing technology of the modern century into their works, as the chapter “Learn Where The Meat Comes From” shows. Signs of experimentation of the critical taboos from “Threat and Sanctuary” are evident in these works, as many artists turned to performance narration captured in film. Although in its early stages, video technology became the primary tool to document and give voice to women and people of color who were sociality silenced. There is a division between artists focused on the formal and technical video elements and by a generation of feminist artists wanting to use the medium to break down power structures in mass media.

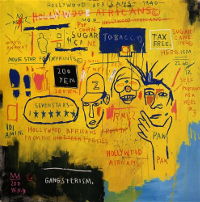

In “Learn Where the Meat Comes From,” Susanne Lacy impersonates a Julia Child cooking show. Lacy begins by normally preparing a meal, and over the course of the video, transitions to madness. Her deranged devolvement is commentary on the portrayal of women’s work and degradation of the female body in the media. Lacy’s work is the title of this chapter due to the representation of the power of performance art as an act of expression and protest. Other installations near Lacy’s delve into similar issues. Artists Cindy Sherman and Laurie Simmons use the still-image to confront concepts of boundaries and identity. Howardena Pindell, from the Los Angeles collective Asco, explores media’s manipulation of racial and gender identities and consequential biases in her 1980 film “Free, White, and 21.” The next-door chapter, “Racing Thoughts,” confronts visitors with a confusion of energized street vibes, parodied consumerism and media-centrism. This powerful art movement of the 1980s was instigated by an economic upswing only felt by the politically conservative - making Wall Street tycoons heroes and over-consumption the norm. Those creating art in this decade were raised under the impersonal spell of Pop art and surrounded by a society obsessed with living a work-hard-play-hard lifestyle. Artists employed media-saviness and techniques of representation that inquired about authenticity and originality in a time of recycled ideas and images. The disparity inspired a movement. Many of the works displayed incorporate readymade products, especially in those of Charles Ray and Jeff Koons. In a Material-Girl fashion, these artists employed actual consumer projects into their works, persuaded by the idea that art’s value was not in its meaning but in its monetary worth. This loss of feeling towards the art is poignant in Louise Lawler’s photograph of Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe at auction. Allusions to art historical references are also seen in the works of Barbara Kruger and Sara Charlesworth. Graffiti works by Keith Haring and Jean-Michael Basquiat toy with the influences of marketing and the television glow.

The adjacent heartbreaking chapter, “Love Letter From The Warfront,” documents the strife of the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s, particularly upon the artistic community. Artists turned into activists, using their craft to bring awareness and to support to the friends, family, and lovers in their community and beyond. Donald Moffett’s “He Kills Me” print, pasted to the opening wall of the gallery, acts as a politically targeted message, criticizing Reagan’s nonchalant attitude towards the crisis.

Many of the works on view were the targets of cultural warfare with religious and political conservatives who deemed their work as too risqué. David Wojnarowicz was one of those vilified for his controversial art. “Untitled,” one of his works in this chapter, is a photograph of an emaciated man on his deathbed. The picture is shocking and not for the light-stomached, yet beautiful with the captivation of a man succumbing to a combative illness. As a whole, “Love Letter From the Warfront” is not intended to be shock-matter material, rather as the Whitney eloquently explains, it is “a more intimate and poetic meditation of the AIDS crisis and the creative community it devastated.” There are a tremendous amount of loss and love, and many feelings in-between, radiating from this memorial gallery space. Unfortunately, by the late 1990s, all of the artists featured in this room had died, but their messages live in on in the powerful art they left behind. The story behind the chapter “Guarded View” begins with Critic Christopher Knight’s review of the 1993 Whitney Biennial. Knight condemned the exhibition’s artistic quality, while strangely noting the novel amount of works by gender, ethnic, and sexual minorities. In 1994, The Whitney’s show “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art” was likewise controversial. Artists such as Jimmie Durham, David Hammons, Mike Kelly and Lorna Simpson were exhibited in these shows exploring identity from sociological perspectives: evaluating culturally-shaped identities and how constructs of race and gender impact our self-images.

The majority of the works in this chapter deal with body as a place of “contest, ideology, desire, or disgust,” says the exhibition’s wall text. Catherine Opie, in her “Self-Portrait/Cutting,” has her back to the camera lens, forcing a viewer to look at her as an individual or type. Like an anthropologist researching an ethnography, other works unfold how everyday objects and images create our sense of self. Mike Kelley’s crazed doll installation uncovers how objects form a young girls inclination towards “teenage fandom and feminine power and allure.” Reaction to conservative criticism of these exhibitions as abandoning traditional aesthetics expanded the understood parameters of what is beautiful in the body and in art. A quiet and small gallery titled “Distracting Distance”

deals with the impact of the digital revolution on the way we inhale

and produce images. Although our technology has changed rapidly over

the years, the works displayed suggest that we are in fact still living

in a transitional Many of the works purposely misuse outdated digital technologies for aesthetic purposes. Kelley Walker’s series mixes up past vintage Volkswagen advertisements with modern modeling software. The artist screen printed the 21 pieces by hand. Cory Arcangel’s “Super Mario Clouds” projects an animation of cartoon clouds from the memorable Nintendo gaming system any Millennial knows well. These pieces invoke a desire for bygone movements and styes, but at the same time a distance from them. This emotional mixture forces the viewer to internally inquire if with each modern advancement, something meaningful is left behind. The chapter “Course Of Empire” derives its title from an Ed Ruscha series. Ruscha’s painting in the gallery, titled “The Old Tool & Die Building,” with its illegible Asian writing, displays a consumed industrial building. Ruscha’s series tells the tale of an American factory taken over by new owners and graffitied, symbolizing of a shift in order similar to the Japanese takeover of the steel industry in the United States in the late 1960s. The canvas serves as an ominous reinterpretation of Thomas Cole’s mid-1800s paintings chronicling a civilization’s rise and its war-riddled fall. From Y2K to this day, the dominant image of American society and politics was fractured in the eyes of the global audience. Artists of this new era recorded changes resulting from 9/11, Middle Eastern wars, the 2008 financial crisis and the looming threat of climate change upon our way of life. Canvases of disturbed landscapes line gallery walls from Carol Dunham’s “Large Bather (quicksand)” to Mark Bradford’s “Bread and Circuses.” The image of a picturesque American society is challenged with these scenes, which reveal a seedy underbelly of deep-seated issues that just get worse with neglect.

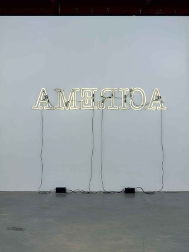

While anxious and distrustful feelings fill the majority of the chapter, hopeful rays shine through. An intimate moment between the first Black President and his wife is revealed in Elizabeth Peyton’s “Barack and Michelle.” Glenn Ligon’s neon relief sculpture “Rückenfigur” reminds us that our country, in Ligon’s words, is both a shining beacon and a dark star. It is a poetic reminder of the strong sense of nationalism, and at the same time alienation, felt in this country. “Get Rid Of Yourself” is a unique section in the “America is Hard to See” show. It is a shifting exhibition space which shows two programs alternating daily. The programs were formulated to counter recent shifts in American culture and its political arenas. Program A shows films interacting with popular culture including advertisements, music, dance and technology. Program B is formed around politically inspired works, undertaking themes of mass media’s role in shaping social and cultural consciousness; the politics of race, gender, and sexual identity; and the potential perils of global capitalism. The film, which the chapter’s name derives from, was made by the art collective called the Bernadette Corporation. Inspired by the anarchist protests at the 2001 G8 summit in Genoa, Italy, the Bernadette Corporation artists used film to evaluate “decentralized, anonymous political resistance and (rhetoric)” and the conversation it evokes. The protesters call to literally get rid of themselves harps on the fruitlessness of individual effort and a global unrest in a Post-September 11 society. The dual programs run their courses each day. Program A is shown Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays; Program B is projected on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. “America is Hard to See” is the new Whitney’s inaugural show running until September 27, 2015. Breaking down the show in its entirety required a series of articles which is finally at its end. For you to meaningfully absorb this monumental exhibition, I recommend spreading it out over the course of two days. For busy New York types needing a cultural boost, I suggest breaking it down over the course of a Thursday and Friday. When the clock strikes five, slip on comfortable sneakers and head down to the Museum for a whirlwind Thursday artistic date night. Admission is $22 for adults; is $18 for students and seniors; and is free for those under 18 years old. Thursday night you should take on the First, Eighth and Seventh gallery spaces. Have a romantic dinner with great views of the Meat Packing, between the first and eighth floor “chapters,” in the Eighth Floor Studio Cafe. You’ll go to sleep with a craving for more American artistic innovations; and the perfect time to finish taking in “America Is Hard To See” would be during the “give as you wish” hours on Friday night. Commence the evening at 6:00 pm by enjoying a fine meal in the first floor restaurant called “Untitled,” and people-watch passers-by on Gansevoort street. During this visit I advise visiting the Sixth and Fifth floors, taking periodic rests in the sitting areas. For those inclined to seeing the exhibit in one day, Saturday is stupendous offer allowing patronage in the morning, afternoon or evening. After a morning or afternoon visit, take a leisurely stroll on the Highline Park. [Julia Slaff]

|