CURATOR'S CHOICE SM

Exhibition Reviews

| Home | | Museum

Guide | | International |

| Theater |

Julia Slaff

| The “new” Whitney Museum of American Art Exhibition,“America is Hard to See:” Eighth and Seventh Floors (May 1 - September 27, 2015) Eighth Floor “America is Hard to See” is displayed throughout the new downtown Whitney location. The eighth floor is a continuation of the exhibition, displaying early works from the vast Whitney collection. Paintings, sculptures, prints, and photographs from 1910 to 1940 are shown throughout the Hurst Family Galleries. The chapters on display are “Forms Abstracted,” “Music, Pink and Blue” and “Machine Ornament.” The elevator ride up to the eighth floor is its own work of art. The inside of the express elevator to the top floor is painted to be a large animated wicker basket. Patrons are carried to the eighth floor like rolls of french baguette.

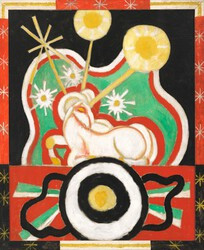

Departing the woven-basket elevator, the chapter one encounters is “Forms Abstracted.” The top-floor gallery has natural lighting from the overhead skylight with white walls and light wood-grained floors. The space is paradoxical to the dark and muted colors of the abstractions adorning the walls. “Forms Abstracted” is named for a 1913 Marsden Hartley painting. It contains a fusion of fragmented cubist forms and bright German Expressionist colors. The European Avant-garde is the primary inspiration for these artists, who saw this movement abroad and in New York. Many of these American artists reproduced this style, or adapted it to express America’s quickly evolving culture. The works show how these artists incorporated Cubist and Futurist influences for portraying American subjects from baseball to cocktails. Many artists touched on modernism in a non-objective manner, backing away from recognizable objects to invent new abstractions.

Each floor is designed for neat crowd flow from one gallery into another. The preceding chapter is titled “Music, Pink and Blue No. 2” for a 1918 Georgia O’Keeffe painting. The art in this section is ruled by a powerful metaphor popular with many 20th Century artists, Synesthesia. Synesthesia is a neurological syndrome in which a person’s senses are altered; one can hear colors and see sounds. Russian artist Kandinsky was famously afflicted. O’Keeffe stated that American artists were deeply interested in “the idea that music could be translated into something for the eye.” Works in this chapter play with this analogy amid music and visual art forms, and for the first time gave artists a simpler explanation for abstraction. The synesthetic idea also opened up inquiries into the concept of non-objective art, presenting shapes and colors without underlying meaning. As the wall-text says, a movement commenced in this time of visual artists relating to music, and composers and choreographers who were inspired by visual artists.

“Machine Ornament” is the eighth floor’s final chapter. The works within this section were made between the first and second World Wars, when industry defined American life and was as important as religion was in Medieval Europe. The pieces vary in their depictions of industry, with representations of haunting smoke stacks to elegant noir style photographs of art-deco skyscrapers. Using industrial subjects as representations of this “Machine Age,” artists such as Charles Sheeler, Elise Driggs, and Charles Demuth depict dirty industrial objects in their purity, lacking the judgment of begrudged craftspeople who's own industry was taken over.

The artists of this time used their art as a means of expressing societal woes towards their changing world. These artist's critique of industrialization is apparent. There is a milieu of alienation towards urbanization with minimal human depictions and lonely renderings of stagnate machines and buildings. Needless to say, the pieces displayed in this section are far from superficial images of industrialization; rather, they are soulful glimpses into the gambit of emotions from loss to glory that tunneled America into modernity. Seventh Floor Following crowds down the pure white staircase, we land in the seventh floor of the Whitney, which houses works from 1925-1960. Chapters “Breaking the Prairie,” “Rose Castle,” “Free Radicals,” “The Circus,” “Fighting with All Our Might” and “New York, N.Y. 1955” are exhibited on this floor. In the section closest to the exit, dark hued gallery spaces of rich navy blue and medium gray set a quiet but powerful tone.

“Breaking the Prairie,” the chapter with dark harvest green walls, is powerful with its depictions of Western American farming life. Paintings and sculptures line this chapter's walls. They truly encapsulate the natural grandeur and beauty of America. Decades preceding World War II, Hopper and other Hudson School artists became increasingly fascinated with “abstracting” America: as a place and idea that could be communicated through expressive images of landscapes and people. Painter John Steuart Curry’s “Baptism in Kansas” takes a religious experience and transforms it into an American experience. His depiction of humble townsfolk dressed in rich fabrics made by American hands sanctifies this religious experience in the setting of a beautiful American landscape. One gets the idea that this is a truly American experience. “Breaking the Prairie” takes ordinary settings and makes them into picturesque scenes. Like in Curry’s powerful painting, other characters such as a boxer or preacher have been transformed into powerful archetypes who are represented in many Americans tales.

The adjoining gray gallery space houses the “Rose Castle” chapter illustrating the American Surrealism movement that occurred during the 1930s and 1940s. Though these artists were all classically trained, Surrealists used the term realism in a different context from its traditional definition. They understood it from a broad perspective, using realism to make “believable depictions of the observable world.” Inspired by famous surrealists such as Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, these American Surrealists explore the connections between real and imagined and making the ordinary unusual. Painters such as Jared French and Louis Guglielmi rendered iconic American images through a dream-like lens. Unusual urban scenes and country landscapes are rendered with a photorealistic style but include odd creatures, especially seen in Guglielmi’s 1941 painting, “Terror in Brooklyn.” A less extreme, but still unnerving, example of these surrealist urban-scapes include George Tooker’s “The Subway.” The works are taken from our world, and at the same time, are removed from it.

Walking into a dark room, one discovers the “Free Radical” chapter. The section is dedicated to filmmakers from the 1930s to the 1950s working outside of the commercialized Hollywood realm. These filmmakers are split between two focuses. Some experimented with concepts linked to painting, like Mary Ellen Bute in the 1930s. She crafted “visual symphonies” set to classical music, making abstract synesthetic paintings come to life with her “Synchrony No. 4: Escape.” Her films, like many others in this section, embody the spirit of full-bodied abstraction gaining popularity in the American art scene at the time. Others used film to explore psychological, philosophical, and even ritual experiments. Helen Levitt, a Surrealist filmmaker wrote, produced, financed and distributed her film “In The Street.” Her Spanish Harlem based film has a documentary style - but it is not that simply understood. In the film’s introduction she states that “[everyday street life is a] theater and a battleground… where every human is a poet, a masker, a warrior, a dancer.” Derek’s powerful approach to presenting everyday life as a staged production is similar to the drama of “Baptism in Kansas” but with the added dimension of the moving picture.

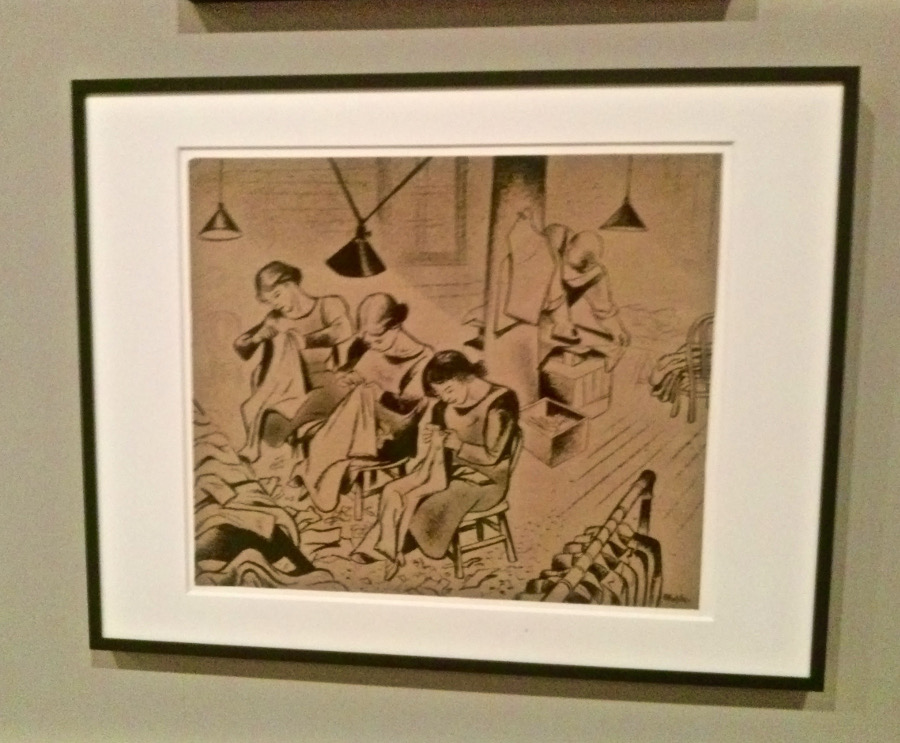

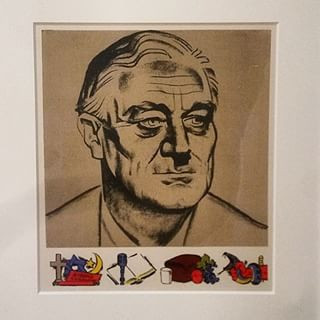

The seventh floor’s “The Circus” chapter orbits around an oval-shaped glass case filled with miniature circus tents and wire-formed carnival performers and animals. Alexander Calder created this large sculpture from 1926-1931 during a time of opulence and social prosperity following World War I. Calder’s installation was influenced by the vast appetite for entertainment and amusement. As the Whitney eloquently wrote, the art reflected in this section expresses the “seen and being seen” theme that wove itself through the American psyche. Many of the pieces shown are in dim settings, lit only by flamboyantly colors, spotlights and signs surrounded by broadway-esque lightbulbs. They range in personalities from great performers such as John Coltrane and Jessica Tandy to normal folks posing as though they were celerities. Strolling through a large entryway from "The Circus," the “Fighting With All Our Might” chapter evokes a more solemn tone. October 29, 1929 is the date that this section revolves around, the catastrophic stock market crash beginning the Great Depression. American artists documented the landscape of homeless families, shantytowns, soup kitchens, protests, and lockouts, hoping to end the unfortunate reality. Artists joined government funded programs created by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, which reinvented and balanced the economy by making jobs and helping small businesses and farms.

Unlike the flashier works in “The Circus,” “Fighting with All Our Might” showcases prints and photographs with similar bold tones and compositions, but with angry and forceful evocations. Photographer Walker Evans was hired for the Resettlement Administration to document life on the farm and Federal Art Project printmakers made over 11,000 prints. Many of these creative people agreed with FDR’s progressive agenda, however others turned to the Communist Party. This chapter shows how art turned from exhibiting American prosperity into a tool of showing aggression and Social Justice.

The “New York, N.Y., 1955” chapter follows the time after World War II when artists asked themselves: “How could art be meaningful in the wake of such a tragedy?” Artists of this era felt forced to act, abandoning the rules of the Western European painting tradition and creating something new. Abstract Expressionism was the result of this existential crisis, which was an art movement that was completely American. Surrealism, European in origin, was a predominant inspiration which encouraged the exploration of the psyche with individual symbolic languages, automatic drawing, and attributing of human characteristics to animals or humans. These Abstract Expressionist components can be seen in the paintings of Arshile Gorky’s 1947 “The Betrothal, II” or Willem de Kooning’s 1952 - 1953 “Woman and Bicycle.” Artistic archetypes of Abstract Expressionism, such as Jackson Pollock, displayed the friendship of materials and application processes with splattering and spraying to evoke spontaneity, exemplified in his work “Number 27” from 1950. The paintings and sculptures within this chapter demonstrates these artists attention to scale in different dimensions, not only to canvas but also to stroke application and color manipulation. [Julia Slaff]

|