CURATOR'S CHOICE SM

Exhibition Reviews

| Home | | Museum

Guide | | International |

| Theater |

"Sultans of Deccan India, 1500-1700: Opulence and Fantasy" By Rosalie Baijer "Sultans of Deccan India, 1500-1700: Opulence and Fantasy" is aptly named. Opulence and fantasy perfectly characterize the art of India’s Deccan courts during the rule of its sultans in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. India was divided in the five sultanates: Ahmadnagar, Berar, Bidar, Bijapur and Golconda. Welcoming to outside influences, the Deccan became home to Persian immigrants, Sufi mystics, Shiite Muslims, and European traders. The diamond-rich region attracted artists, poets, writers, and traders from all over the world. They came from Iran, Turkey, Africa, and Europe and were drawn to the Shi’a culture and material splendor of the five sultanates. These five courts were successors to the Bahmanid Empire (1347–1538), which had unified the Deccan under Muslim rule. This exhibition, a mixture of all these regions and cultures, brings together two hundred of the finest works from major international, private, and royal collections. The exhibition is showing the art of the five sultanates of the Deccan, each in its own room.

As you enter the exhibition, the sparky diamonds of the rich region immediately amaze you. In the first gallery's exhibition, "Diamonds of the Deccan," the most precious jewerly is shown. The "Idol’s Eye," "The Arga" and other diamonds from the extremely rich mines of Colconda were used in the magnificent gems of international royal collections. The next room is showing us two of the sultanates, Ahmadnagar and Berar, and the history this Bahmani Legacy. The art tells us a historical story by portraits of many different rulers and images of traditions. With different objects from foundations of Bahmani buildings and Ahmadnagar drawings, the artists reveal distinctive styles. This is where Deccani art was born. A small group of surviving drawings from Ahmadnagar reveals a taste for such fine works. Persian artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had developed a variety of drawing methods and these techniques flourished at Ahmadnagar. "Royal Elephant and Rider" (Ahmadnagar, 1590–1600) really brings the elephant alive. The rider's expressive face and the elephant's royal robe, decorated with fine art, exemplify the style. A magnifying glass is offered for close inspection.

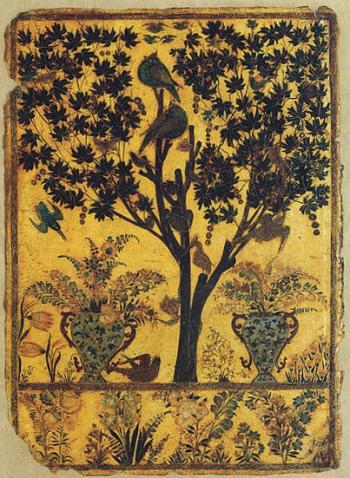

Bijapur was one of the largest of the five sultanates and ruled by cultured sultans who were passionate about music, poetry and painting. The floral fantasies are eye-catching. Imaginary blossoms were a favorite subject for Deccani artists. Such creative exercises belong to a tradition that extended across the Ottoman, Persian, and Deccan worlds, tied together through the use of arabesques, sinuous lines, interlocked leaves and fantastical motifs. "Pair of Book Covers" gives us the perfect illustration of the imagination of these artists. Insects appear in the same size as birds among high-growing flowers.

The metal work of Bidar, located in the heart of the Deccan, was influenced by Persian, Mughal, and Turkish design and displays a startling originality unique to its places of origin. The Bidri works are warm and fragile works, mostly inspired by the onion tops we see in small tombs and mosques. "Bidri Carpet Weight (Mir-i Farsh) with Trellis Pattern" (Bidar, 17th century) is made of Zinc alloy inlaid with brass and silver and was used to hold down lightweight cotton floor coverings. Its fine technique, detailed decoration and use of colors make it a decorative and useful piece of art.

Golconda was on the south east side of the Deccan and the land of diamonds. With rich and fertile farmland,Golconda was very attractive for European traders.The art of Golonconda tells us a lot about the traditional culture of the Deccan. We see many figures, flowers, and animal creations in decorative mortars, vessels, calligraphies (Alams) and hanging kalamkaris. Kalamkaris are textiles of the Deccan made for courtly patrons. Calligraphics demonstrate the art of drawing with phrases of Arabic prayers rendered in calligraphy. These objects reveal a much more playful side of the art.

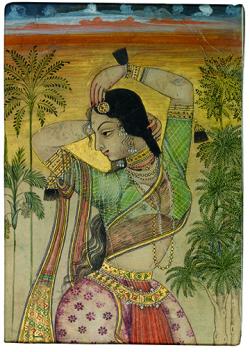

The section "Mughals and Europeans in the Deccan" shows evidence of the attractiveness of the Deccan for merchants from around the world, who arrived along east-west trade routes. First came the Portuguese, followed by the English, Dutch, Danish and French. In 1687, the last of the Deccani sultanates was defeated by Prince Aurangzeb and its lands were annexed to the Mughal Empire. Artists and their art were transported north, where they inspired later generations of artists and extended the legacy of the Deccan’s golden age. "Meeting of the Dutch and the Danes in the Deccan" is an scene drawn in kalamkari. This lively scene illustrates the multicultural environment of the Deccan in the seventeenth century at its best, with a scene of the Dutch proposing to buy the Danes' fort. In the Palanquin Finials (Golconda, ca. 1650–80), we see miniatures of the golden flowers upon which royal passangers were carried. And the "Dancing Girl" (Golconda, late 17th century) shows us an classical Indian maiden dancing, wearing Indian clothes with traditional imperial jewelry.

In every court, independently of the art, there are beautiful photographs by Antonio Martinelli representing present day scenes and clearly demarcating the individual sections of the exhibition.

IF YOU GO

|