THE MET and its Brush with Vallotton

By Lyle Andrew Michael

Félix Vallotton:

Painter of Disquiet

The Met Fifth Avenue

(212) 535-7710 or www.metmuseum.org

Oct. 29, 2019 to Jan. 26, 2020 from 10:00 AM daily.

Reviewed by Lyle Andrew Michael. Oct 29, 2019

|

| Félix Vallotton, The Sick Girl (La Malade), 1892. Oil on canvas. 74 x 100 cm. Photo by Lyle Andrew Michael |

The disconcerted faces of Gertrude Stein--one by Picasso and one by Vallotton--look away from you while the pallid 20-year-old visage of Vallotton meets you in the eye at this striking display of his artwork depicting Paris through his unusual lens: tumultuous, unscrupulous, provocative, evocative and beautiful all at once. Disquiet is the accurate term to describe Félix Vallotton’s exhibition, the first of its kind in America in nearly 30 years.

Prior to this showing of fin-de-siècle Paris, most art enthusiasts like us were unfamiliar with the works of Vallotton. Thanks to the MET, the Royal Academy of Arts, London and Fondation Félix Vallotton, Lausanne, the Swiss-born Vallotton (1865–1925) who left home at 16 to study art in Paris, and paint Paris with mordant wit and humor, will remain impressed on the mind.

Back to Stein, the Vallotton version of the portrait of the famed novelist and art collector rivals the Picasso signature as they hang side by side at the MET. The two could not be any more dissimilar, hence rival might be incorrect. The Vallotton commission by Stein reveals a stern and remote appearance, highlighted by her ample frame, rendered with cautious abandon by the artist who started from the top of the canvas across. “Take that as you may,” said Dita Amory, curator in charge. Along with Ann Dumas, curatorial powerhouse at RA, London and Katia Poletti of the Vallotton Foundation, there was enough background knowledge to supplement the message and tone of the artist, vividly presented in his work.

His mission: to delve into Paris’ dark side at the end of the 19th century and reveal the duplicitous nature of its society. Vallotton’s tone is direct, castigating the doers for their actions and the powers that be for their inaction. What you get then is a series of portraits, personal life, domestic scenes, still lives, nudes and landscapes through a variety of media, techniques and palettes.

|

| Félix Vallotton,

The Visit (La Visite), 1899. Gouache on cardboard. 55.5

x 87.0 cm. Photo by Lyle Andrew Michael. |

What stands apart is the Intimite series - which focused on the life

of the bourgeois behind closed doors. “The Lie” is perhaps

the most popular of this lot. It was later recreated as an oil on cardboard

in color, in which the red hue stands as a stark symbol of deception.

This private moment is given a lined wallpaper background which can well

be seen as some order in the chaos. Intimite went on to be published in

La Revue Blanche (1898), the avant-garde journal that Vallotton got involved

in prior to his time as a member of Les Nabis (the prophets), alongside

predecessors Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard. This group of young

artists typified the movement from impressionism to symbolism and more

abstract art, and Vallotton earned himself the moniker of the “foreign

prophet” for his more singular aesthetic view.

|

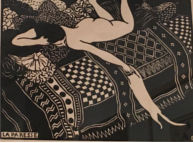

| Félix Vallotton, Laziness

(La Paresse), 1986. |

Vallotton had embraced engraving on wood — from European and Japonism art — in a lot of his work. Among his larger selection, the most scandalous — if one might use the term in an art space – is the assassination of French president Sadi Carnot by an Italian anarchist. “L’Assassinat” (1893) is a masterful use of black ink - primarily to create the criminal’s figure in action - on wove paper in a definitive line space which unexpectedly offers an unequal image. Such is the power of the monochrome and flat lines.

Still life was another specialty. “Red Peppers” (1915) on a white lacquered table with a bloody knife grabs the eye first. This image, with its simplistic usage of lines and color, is evidently symbolic of his disdain with World War I and the fact that he wasn’t allowed to enlist in the army due to his age (48) though he was a French citizen.

|

|

Félix Vallotton, The White and the Black (La Blanche et la Noire), 1913. Oil on canvas, 114 x 147 cm. Photo by Lyle Andrew Michael |

Yet another of his specialties, with around 500-plus paintings recorded, is his somber portrayal of the female nude figure. “La Blanche et la Noire” (1913) stands imposing at the exhibition and begs the question, “What was Vallotton’s intention with this painting of a white mistress with her black maid in a rather ambiguous telling?” The former lies nude and half asleep while the latter commands the frame with a cigarette between her lips. Once again Amory suggests, “Take that as you may.” Inevitably, it invites comparison with Manet’s “Olympia.” Yet the two are quite opposed in the techniques used and portrayal of the women. Vallotton’s oil on canvas is less perfect; his nude is exhausted and the maid is authoritative.

Unusual, unabashed, ambivalent; that’s Vallotton: the printmaker, illustrator and painter of disquiet who eventually married into the very bourgeoise, high-class circles he denigrated and established himself well though his wealthy and well-connected partner, widow and mother of two. Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques, is shown in a large oil on canvas seated on her couch in a white gown with her hair up, her face detached from the viewer and her posture un-ladylike.

|

The paintings that Vallotton did as a husband and stepfather throw light on a semi blissful domestic life. “Dinner by Lamplight” (1899) is hauntingly beautiful portraying a family meal, seen from over-Vallotton’s-silhouetted-shoulder, as he looks ahead at the face of his young, fearful stepdaughter. Detailing in the lampshade further reveals that Vallotton was also a lampshade painter.

Vallotton drew inspiration from artists before and of his time — the post-Impressionist styles of Paul Gauguin, for one — yet he was an artist quite rare in his execution, who defied societal conventions, made clear his political views and laid out his personal life through the peculiar stroke of his brush. “Disquiet” reveals this admirably.

He was a set designer for Strindberg's and Ibsen’s avant-garde productions, too. What a great topic for another exhibition!