Museums and Exhibitions in New York City and Vicinity

| Home | | Museum Guide | | International | | Architecture & Design | | Theater |

GLENN LONEY'S MUSEUM NOTES

CONTENTS, May 13, 2000

[01] More "Making Choices" at MoMA

Caricature of Glenn Loney

by Sam Norkin.

[02] Vienna's Albertina at the Frick

[03] Magnum Photos at NYHS

[04] Collectors as Patrons at Knoedler

[05] Mary Griggs Burke Japanese Art at Met

[06] African Art & Oracles at Met

[07] Met's New Cypriot Galleries

[08] "American Modern: Design for a New Age" on the Way

[09] In Sachsenhausen & Berlin, Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

For editorial and commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010. Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

Copyright © 2000 Glenn Loney.

For a selection of Glenn Loney's previous columns, click here.

More MoMA "Making Choices"

[Closing September 26]

| |

| HANDS UP FOR SOCIALISM!--1930 Propaganda Poster by Gustav Klucis, on view at MoMA's "Making Choices," as an example of "The Rhetoric of Persuasion." | |

The various demonstrations of MoMA curators "making choices" are generally limited to four central decades of modern experimentation in art, design, and architecture. Some related objects and artworks which were created before or after are included to provide a useful continuity.

Few developments in the arts come immediately and entirely out of nowhere. Dada may be an exception. And maybe Jackson Pollock?

Nor do major movements come to a sudden end, as if someone had flicked a switch. Like Old Soldiers, some just die away.

Actually, though it's tempting to explain these MoMA installations as the choices of its curators—which they certainly are, as are the often quixotic titles for various groupings—the artistically important choices were made long ago by the artists themselves.

Here's MoMA's rationale, so you will have an idea of what to expect:

"At any given moment, artists confront divergent opportunities and challenges, defined by the art that has come before and by the changing world around them. Each artist responds differently; competing programs and imperatives sharpen those differences; and independent traditions in particular mediums further nourish variety. Even the art that in retrospect seems the most innovative is deeply rooted in the constellation of uncertain choices from which it arose. Modern art is justly celebrated for its spirit of ceaseless invention; these exhibitions aim as well to stress its vital multiplicity."

Yes. I could not have said it better. Rhetorical deficiency only one reason I'm not a curator.

On the fourth floor, the smallest of MoMA's major galleries, there are only three themed exhibitions. They are "The Marriage of Reason and Squalor," "The Raw and the Cooked," and "Useless Science."

These are the kind of supercute titles that seem to drive art-critic Hilton Kramer wild. They only add fuel to his burning irritation with the apparent abandonment of curatorial grouping by eras, cultures, or movements and schools.

There will be more of this innovative "narrative" organization, not only at MoMA but also at the New Tate in London and in Paris at the Centre Pompidou. It offers seasoned gallery-goers a welcome opportunity to look at older works in a new light, in ways they've never considered them before.

And for art-gallery beginners, this is a lively way to experience major and minor artworks for the first time: "Look! The whole room is full of paintings of faces!"

And why not?

Just because the fourth floor is usually reserved for architecture and design—possibly to keep those artifacts out of the way of museum visitors who are only interested in paintings and sculptures—is no reason to avoid that level in the next few months.

My favorite is Useless Science, with its crazy machines and constructions. Among them are Sandy Calder's automated "A Universe," Marcel Duchamp's "Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics)," and Panamarenko's "Flying Object," a really Alien spacecraft.

Several local galleries and museums have recently had special shows to consider the differences between truly "naive" artists and those trained talents who have deliberately adopted a primitive, even brutal, style to achieve unique effects.

Then there are folk-artists who are not always "naive." Folk-art traditions can become very highly evolved, even sophisticated. What was "primitive" in African or Asian folk-art to Western eyes a century ago, was certainly neither naive nor primitive to the artists who made it.

In "Raw and Cooked," it's suggested that some fake-naive artworks were made "to get the public's goat." Abstract Expressionims and Minimalism have been far more successful at that.

Closeted doodlers, seeing this show, will be encouraged to regard their odd squiggles as potential submissions to MoMA's graphics collection. I might just donate mine—if I don't give them to the Jung Foundation.

On the much larger third floor expanses, the shows include: "Anatomically Incorrect," "How Simple Can You Get?" "Seeing Double," and "The Rhetoric of Persuasion."

The last of these permits public display of bold dictatorial poster-art. But, at "this point in time," MoMA is not worried that you'll rush out to join the Nazi Party, the Falange, or Mussolini's thugs.

Still, they had powerfully designed posters and banners, all of them. Hitler, in fact, copied the Soviets' bold use of red in flags and posters. Hugh Trevor-Roper quotes him on this in "Hitler's Table-Talk."

Some of the anatomically skewed images are either hilarious or disgusting, depending on your mind-set. An odd torso sculpture, for instance, is centered on a rounded belly, with pelvis, vagina, and chopped-off legs at both ends. This is Hans Bellmer's "Doll." You can't miss it.

Home-Movies even have their moment in "Making Choices." As does the distinguished photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, with selections from his work after World War II. He was a founder of Magnum Photos—which is currently having a major exhibition at the New-York Historical Society.

Furniture designs of Charles Eames can hardly be overlooked, so his 1948 Chaise Longue has been assigned to "Modern Living 2." But the best creations of European artists and craftsmen are also included here.

Ban's Paper Arch:

In addition to the stimulating gallery shows, an amazing construction, created just for MoMA and this exhibition, has been erected over the central section of the museum's sculpture garden. This is Shigeru Ban's "Paper Arch."The structure weighs nine tons and arches 87 feet across the garden, creating a kind of diamond-hatched open roof. Nine tons may seem a lot of paper, but the basic building-material is really paper rolled into specially constructed cardboard tubes.

The sturdy interlocking tubes are all weather- and fire-proofed. Whether the arch can withstand a New York winter is not in question. It will be dismantled in August.

Of course the tubes aren't just glued together and perched on roof-gutters and garden walls. A complex and sleekly engineered system of cables, turnbuckles, and steel framing keeps the entire structure in place.

Ban has also designed a paper-made structure for the Japanese Pavilion at EXPO 2000, to open June 1, in Hanover, Germany. Major themes of this World's Fair are enlightened uses of natural resources and protecting the environment.

Ban's paper buildings are all designed for recycling. But they are by no means Houses of Cards. After the terrible Kobe Earthquake, he devised inexpensive, easy-to-construct temporary housing from paper-products.

Vienna's Albertina at the Frick

[Closing June 18]

| |

| FINE ART FREEWAY AT THE FRICK--Actually, this spacious skylit space is formally known as the West Gallery. It contains some of the most important paintings in the Frick Collection. Photo: ©John Bigelow Taylor/Frick Collection. | |

When I first came to Vienna, in the mid-1950s, when scars of World War II could still be seen everywhere, I was nonetheless able to visit the Albertina. I wanted to study some original drawings for the Vienna Court Theatre and the State Opera.

For a student of Theatre History—and a lover of music—it is a magical moment to hold in one's hands the original set-renderings for the premiere performance of a Mozart opera.

Expecting to be denied, I then asked if I might see Albrecht Dürer's famous drawing of a rabbit. After a short wait, I was holding this in my white-gloved hands. To protect the original, of course.

| |

| AGE & WISDOM--Albrech't Dürer's 1531 study of a 93-year-old man, currently on loan from Vienna' Albertina to New York's Frick Collection. | |

The treasures of the Albertina seem boundless. So it must have been difficult to make curatorial choices for the 45 master-drawings to be sent to New York's Frick Collection.

The aim was to provide an overview of five hundred years of masterworks: from Dürer, Michelangelo, and Leonardo, through Rubens and Rembrandt, to Picasso, Klee, Klimt, and Schiele.

Selections have been both representative and breath-taking. Among them are Dürer's "Head of an Old Man" and "The Rider."

This mysterious knight in armor rides through a strange thicket, with demons glaring and a skull on the ground. As I write this, I'm also looking at a copy of this image, cast in aromatic beeswax, and purchased many years ago in Vienna

But not at the Albertina Gift-Shoppe. They didn't have that kind of art-consumer amenity then.

Fortunately, the Frick has an excellent small shop, with a wide selection of art books, posters, and reproductions. You will surely want to have Barbara Dossi's handsome book: "Albertina: The History of the Collection and Its Masterpieces."

Published by Prestel Verlag in Munich, even the paper-back edition is sturdily bound and, of course, printed on heavy paper of the highest quality for reproductions. There are 192 pages, and the volume costs $45.

This is much more than a catalogue of the current exhibition. It opens with a very interesting account of the collection's origins and subsequent development.

The name "Albertina" may suggest some Imperial Austrian Princess. Or even an Empress of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Not at all. The basis of the collection was formed by the art-loving Duke Albert, of Saxe-Teschen.

He was the llth of the 14 children of the Prince-Elector of Saxony. [Electors got to vote for the next Holy Roman Emperor when the previous one had died.]

By the Rule of Primogeniture, the first son inherited everything. So Albert was too far down the sibling-ladder to hope for any handouts in Dresden.

He presented himself at the Imperial Court in Vienna, where his appearance, intelligence, good-manners, and admirable disposition made him an immediate favorite.

And he married well: the favorite daughter of the Empress Maria-Theresia. She had the money necessary for the building of a great collection. Duke Albert was a shrewd collector of individual works. But he also was able to acquire other distinguished collectors' treasures.

In 1920, his and the Imperial Court Library collection were combined to form the Albertina. The Duke had, at his death, collected 14,000 drawings and 230,000 prints.

The combined collection is known officially as the Graphische Sammlung Albertina. It now preserves some 65,000 drawings and a million prints. These span the late Gothic to the present, representing all major regions of artistic creation.

But the span—or gap—between the artistic vision of Leonardo's study for "The Last Supper" and that of Jackson Pollock's black-ink splatter, "Untitled," can be measured in Light-Years, not centuries.

| |

| I DON'T WANT TO SET THE WORLD ON FIRE--But art-collector and museum-patron Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer did want Votes for Women. She is one of the wealthy New Yorkers included in the Knoedler Gallery's new exhibition, "The Collector as Patron." Photo: ©Corbis-Bettmann | |

In addition to her remarkable donations of artworks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer's urge to improve the Quality of Life around her made her an ardent Suffragist.

If anything, she may well have thought that "Votes for Women" was even more important than "Art for the Masses."

In the vertical display compartments allotted to distinguished individual or family patrons, the sumptuous private art-galleries of the Vanderbilts and other Manhattan Robber Barons show walls crammed with paintings from floor to ceiling.

In the photos or sketches, you can barely see the rich velvet or tooled leather wall coverings. The gallery floors are crowded with sculptures, objects-d'art, inlaid Italian marble tables, and overstuffed furniture.

What was most surprising about studying these art-stuffed interiors was to learn that some of them—in Manhattan's most palatial mansions—were open to the public on certain days, at certain hours.

[That is still the rule at the fabulous Albert G. Barnes Collection in Merion, Pennsylvania.]

Considering all the negative criticism, then and now, focused on the founders of Great American Fortunes, some certainly deserve credit for their eagerness to share their treasures with those unable to buy fine art.

Establishing the Metropolitan in Manhattan in the late 19th century—as well as founding free public museums in major American cities—was not just another way to show off a magnate's wealth and power. Or his wife's social position and good-taste.

Of course, those could be added benefits, if one's self-esteem required even more inflation.

Looking at all these photos, letters, and artifacts—largely drawn from Knoedler's 154 years of archives—it is instructive to discover how many of these very rich art-collectors left large bequests of artworks and money to museums for the public's enjoyment.

Often, during the most active times of their lives, they were also donating art and giving funding to museums for the benefit of their communities.

Some famously rich men with equally famous and rich collections—men like Henry Clay Frick and J. P. Morgan—even decreed that their homes or private galleries and libraries be preserved as museums, open to the public.

Among the noble Knoedler clients featured in this show are: Lillie P. Bliss, Charles Freer, Catherine Lorillard Wolfe, Henry McIlhenny, Duncan Phillips, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Andrew & Paul Mellon, Samuel H. Kress, the Arensbergs, the Havemeyers, the Lewisohns, the Huntingtons, the Tafts, the Wideners, and Chicago's Potter Palmer and his wife, Bertha Honoré.

S. H. Kress's bequests of Italian Renaissance artworks are scattered around the United States in major museums. Those not good enough for the National Gallery ended up on the walls of such institutions as San Francisco's De Young Museum.

In the main-floor Knoedler gallery, a number of impressive modern works are on view. Some of these have either already been donated to museums. Some are promised gifts.

Donor-patron-collectors include Agnes Gund, Mary & James Patton, Bebe & Crosby Kemper, and Marieluise Hessel.

| |

| MILTON AVERY'S "SEASIDE STROLLERS"--On view at Knoedler Gallery's "The Collector as Patron" exhibition. Courtesy of Knoedler & Mary and Jim Patton. | |

Other important artists represented include Jasper Johns, Hans Hofmann, Sam Francis, Cy Twombly, Wayne Thiebaud, Mark Rothko, David Park, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning…

But why go on? The painters of the 23 canvases in this show are a Who's Who of modern art.

A pendant panel discussion on "The Collector as Patron" was held at the Frick Collection. Among the luminaries involved were: Charles E. Pierce, Director of the Morgan Library; Jay Gates, Director of the Phillips Collection; Earl Powell III, Director of the National Gallery, and Michael Conforti, Director of the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA.

Admission to the Knoedler exhibition is free. The gallery is located at 19 East 70th Street, NYC 10021. Phone: 212-794-0550.

New at the Metropolitan Museum:

Masterpieces of Japanese Art

From the Mary Griggs Burke Collection

[Closing June 25]

| |

| KANBUN BEAUTY--Detail of Japanese hanging scroll, on view at the Met Museum as part of the Mary Griggs Burke collection. Courtesy of Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation. | |

Obviously, all of those objects and artworks are very much in evidence. But they are among the very best ever created in the island kingdom.

Elegant ceramics, precious lacquer boxes, sinuous sculptures, prints, paintings, and even drums are also on view. There are some 200 individual artworks in this show, a very small fraction of the fabled collection.

The items on display range from 3000 BC to the Edo Period, ending in 1868. In the 37 years of collecting that this show represents, Mrs. Burke assembled the most inclusive and largest private collection of Japanese art outside that country.

Her taste proves exquisite. The glowing four-hundred-year-old folding screen, "Women Contemplating Floating Fans," has never before been exposed to public view.

In paintings and prints, not only are the images of nature, animals & birds, historic architecture, and distinctively costumed men and women arresting in the way the artists have seen them. But they are also rendered with such delicacy and sureness of hand that one must admire both the craft and the art.

These examples from Mrs. Burke's collection show her wide interest in many forms of Japanese artistic expression. Thus, a variety of changing or contrasting styles greets the visitor's eye.

Art and Oracle:

[Closing July 30]

Spirit Voices of Africa

| |

| IT'S IN THE BAG!--Colorful beaded bag for Yoruba diviner's ritual tools, shown at the Met in "Art & Oracle." | |

If you are slightly superstitious, you might worry that some of these sacred objects have not been de-commissioned from their original supernatural functions. Even if they have been in major museum collections for some time.

But this unusual show is not about the Mummy's Curse. Or the stolen Idols' Eye. Pulp-fiction has rather overworked the terrors of religious objects, purloined from ancient cultures for their precious materials or marvelous workmanship.

Nonetheless, some of these strange statues and elaborate divination boards surely still contain some of the mystic powers with which they were originally endowed. We just do not know how to invoke their magic.

If there was any danger in that area, it was rapidly and thunderously dispelled at the press-showing. Standing tall in an intricately embroidered Yoruba robe, Dr. Wande Abimbola chanted invocations to the Ifa, the ancestral god who makes communication between the living and the dead, the present and the past, and the human and the divine possible.

Dr. Abimbola is a babalawo, an priest of Ifa, who can invoke the assistance of Orunmila and other Yoruba deities in divination rituals. At the Met, the Yoruba gods were asked to bless the event and the exhibition. It was very impressive.

Some thirty years ago, I went to Ile-Ife, to its small museum and to its handsome modern university, where Dr. Abimbola was president a decade later. At the museum, I saw some carved doors and ritual objects like those in the current show.

I also bought some striking modern pastels of Yoruba life, including a healing ritual, from the noted artist, Muraina, who was tending the museum collections. Several months later, he was playing in Manhattan in a small combo for a Korean ritual drama at Ellen Stewart's LaMaMa ETC!

When I went to the nearby Shrines of Oshogbo, as the light was dying, I had the strange sense of being watched. I turned around, beside the dark, silent river, to discover a large wooden figure of the river-goddess towering behind me.

Muraina later reassured me: "You are her child. She welcomes you."

Back in Lagos, one evening a trader from Dahomey came by my host's apartment. Toni traded a torn shirt—but with London tailoring—for a carved ivory divination counter. The trader didn't have a board with him, unfortunately.

I traded for a pair of Ibejis. These are small carved wooden images of twins who have died at birth. The grieving family puts the twins in a shrine, where they are offered delicacies and respect.

It may be that the twins were gods—who decided not to stay with the family. A blessing lost. So they may need to be placated, invited to come into the flesh.

My twins were very special, but I took them to the National Museum to obtain permission to bring them back to New York. It took a while, but I ultimately received them with full documentation.

Soon after, Elliot Elisofon photographed them and I wrote a piece about this adventure for "Smithsonian Magazine."

Inspecting this fascinating exhibition took me back, in imagery and memory, to Yorubaland.

But that is hardly the only West African culture represented in the show. And Central African ritual objects are also on display.

Among the most interesting objects is one of the famed Benin cast bronze sculptures. The detail and delicacy of the body ornaments, as well as the distinctiveness of the human features is amazing.

Two loans from Paris museums are especially important ritual sculptures: they are the divination portraits of King Glele and King Gbehanzin of Dahomey, now the Republic of Benin. But not to be confused with Benin City, in Nigeria.

The Met's New Cypriot Galleries

Permanent Installation]

| |

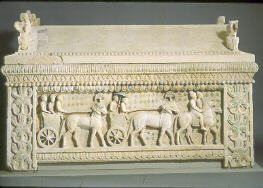

| AWAY WE GO!--Two charioteers on the side of an ancient sarcophagus, in the Met Museum's newly installed Cypriot Galleries | |

He was Luigi di Cesnola, who was able to acquire some outstanding antiquities while serving as American Consul General in Cyprus. These he sold to the newly founded Met Museum in the 1870s.

The Cesnola Cypriot Collection was the Met's first large group of archeological artifacts. Never shown before in this depth or variety—and, in fact, not on view for a while—Cesnola's treasures have been redeployed handsomely in the new galleries.

The sculptures, vessels, ceramics, ornaments, and other fine objects range from 2500 BC to 300 AD. There are no stolen Christian artworks here.

Cesnola was in Cyprus long before modern Turkish rascals and other art-thieves began pillaging the past, hacking Orthodox frescoes from ancient churches.

The objects on view don't represent the cult and cultural expressions of only one people. Cyprus, as a centrally-located island in the Mediterranean, has had a variety of ethnic and tribal influences flow over it.

The Greek Ptolemies left their mark. As the dynasty became rulers of Egypt, under Alexander the Great, Egyptian gods found their way—at least as images—to Cyprus.

A sarcophagus with two two-wheeled chariots on its side-panel—and two men, rider & driver, in each of the cramped boxes—recalls similar Greek and Roman transportation scenes.

| |

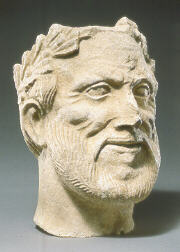

| CROWNED WITH LAURELS--Head of smiling man with beard in Met's Cypriot Galleries. | |

A terra cotta jug, in an oblong barrel-shape, with a neck and bird-head stopper, has lines and designs drawn on it which could have been inscribed by Native Americans from the Southwest. But it is dated sometime before 600 BC. That qualifies it as Cypro-Archaic.

Opening Soon!

American Modern, 1925-1940:

Design for a New Age

[Closing January 7, 2001]

At this writing, it's still two weeks to the Press Preview. I have no advance information on what will be shown, nor how it will be presented. When it becomes available, we'll try to include it in this column.

This Deco Era show opens on May l6. At that time, Met visitors should also check out the reinstallation of the second-floor galleries for permanent collection holdings of painting and sculpture, 1940-1970.

Also in the Lila Acheson Wallace Wing: Klee's Line, After Nicolas Poussin: New Etchings by Leon Kossoff, Century of Design, Part II, 1925-1950, and Painters in Paris, 1895-1950.

You can also see David Smith on the Roof. Or at least some of his sculptures.

Now, reparations for those who worked as slave-laborers in Nazi wartime factories are being prepared. Even some non-Jews may receive some compensation if they have some kind of organization to represent them.

Unfortunately, no one, then or now, cares about what homosexuals suffered under the Nazis. Nor have any who survived Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz, or other Death Camps yet been given an indemnity.

This information is only one of the many unpleasant discoveries one can make in the current Berlin & Sachsenhausen exhibition of the Nazi Era persecution of homosexuals.

Even in the aftermath of the horrors uncovered when German and Austrian Concentration Camps were opened by Allied troops, there was very little concern or sorrow about the torture and murder of both Gypsies and Gays.

Even in America, even now, one can hear the dismissive comment: "They got what was coming to them! It's against Nature and against the Bible!"

Could it be that the Nazis were really doing God's Work, after all? At least with regard to homosexuals?

You won't think that if you are able to study the displays and documentation at KZ Sachsenhausen—infamous for its Death March—and the Schwules Museum in Berlin.

From the end of 1939 to the middle of 1943, some 600 homosexuals were murdered in Sachsenhausen, for example. In 1936, SS Commandant Heinrich Himmler established a special National Central Office for Combating and Rooting Out Homosexuals.

The Berlin-based museum—Schwul means gay—is in the Kreuzberg section of the city. What remains of KZ Sachsenhausen—now a memorial to those who suffered and died there—is outside the town of Oranienburg, near Berlin.

There is even a book for the exhibition: "Homosexual Men in KZ Sachsenhausen."

For information about the exhibition, the catalog, and the museum, there's a website: www.schwulesmuseum.de

[Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2000. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, Curator's Choice." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nymuseums.com.

KZ Sachsenhausen & Berlin:

[Closing July 30]

It is understandable that Jews who survived the Holocaust—or their heirs—should have been paid a reparation, or Wiedergutmachen, by the German government. It is entirely in order that Swiss bank-accounts belonging to Jews murdered by the Nazis should be returned to their heirs.

Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals