CURATOR'S CHOICE SM

Exhibition Reviews

| Home | | Museum

Guide | | International |

| Theater |

| NEUE GALERIE By Claire Taddei

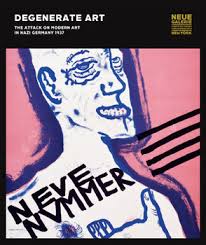

From March 13 to June 30, 2014 the Neue Galerie is presenting "Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937." This is the first major U.S museum exhibition devoted to the topic of "Degenerate Art" since the 1991 presentation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The striking installation attempts to exorcise the Nazis' artistic eugenics. This exhibition is a natural if you know thegallery's artistic orientation.

The title of the exhibition refers to the terminology used by the

Nazis for the "sacrificial" exhibition, "Degenerate

Art" in 1937 in Munich, organised in order to destroy the power

of the Modern artist. By showing Modern artworks alongside those of

the mentally ill, the Nazis wanted to emphasize the Modern works as

regressive and perverse. This exhibition allows us to better understand

the overall process of extermination carried out by Hitler. The art

threatened the single mindedness of the Nazi regime. Hitler understood

the social and political power of art and feared it. In 1935, Hitler

defined what must be art: The first floor of the museum, devoted to the permanent collection, plunges us into the aesthetic world of the art scene in Germany and Austria in the early 20th Century and the beginnings of Modern Art. The atmosphere of this era is conveyed to life with a subtle mix of furniture, decorative art and paintings of this period. The Berlin and Viennese aesthetics diverge yet respond to one another. They feed off of a common desire: to break free from the rigidity of dogma and the classical aesthetic, notably by an abundance of curves, on top of a quasi-absence of perspective – in both the literal and figurative senses. The absence of perspective resonates on the one hand as a lack of perspective for the future, and on the other hand as an opposition to the rules of classicism. In transgressive and subversive manners, sex and death are represented in different ways, in the ornamental style of Gustav Klimt and the starkness of forms of Egon Shiele. On the second floor, reserved for the exhibition, the challenge is to illustrate with only three rooms the totalitarian politics of Hitler, who had censored works, which became some of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art. Indeed, as the "final solution of the Jewish question," Hitler wanted to establish a "final solution" for Modern art, systematic and rationalized. The destruction is bureaucratized, as illustrated by the very strict bookkeeping manages by the Nazis. Stigmatized by the Nazi propaganda as "degenerate artists" because they were too free and totally avant-garde, these artists didn't fit into the pictorial codes of National Socialism. Here, Paul Klee's paintings, judged too childish by the Third Reich are displayed next to Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's works, which were probably too expressive and reflective. There is the subtlety to the exhibition, which establishes a direct link between the concept of "degeneration" and selected artworks. The exhibition tends to reaffirm the ambivalent relationship, almost schizophrenic, that the Nazis had with culture, constantly in tension between possession and destruction. Indeed, the renewed interest in this historic moment follows the revelation last November by Focus magazine of the discovery of the existence of 1,400 works of art (Courbet, Renoir, Matisse, Chagall, Klee, Kokoschka, Beckmann...) in Munich in 2011. These works were hidden in the home of Cornelius Gurlitt, son of Hildebrand Gurlitt, who was one of the Hitler's artistic advisors. The Neue Galerie confronts the Nazis' official art and censorship by putting side by side the neo "Pompier" triptych, "The Four Elements," by Hitler's favorite artist, the painter Adolf Ziegler, and "Departure," a triptych by the implacably modern Max Beckmann. His line is more aggressive and dark, more close to Expressionism. In the basement, outside the restrooms, the walls are plastered with posters from the Vienna Secession group, which sparked the Modern art movment and whose artists were supressed by the Nazis.

In rooms, many empty frames of paintings hung above artworks remind

us of the tragedy of this historical moment.

Claire Taddei is a free lance writer from Lyon, France. Her articles can be found on the artbook store "Librairie Michel Descours" website : http://www.livres-art.fr. If you go:

|