CURATOR'S CHOICE SM

Exhibition Reviews

| Home | | Museum

Guide | | International |

| Theater |

History Through Photography

By Adèle Bossard

Next July will

mark the sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) of the Battle of Gettysburg

and it is soon after the hit of Steven Spielberg's last movie “Lincoln.”

Now the Met Museum offers, in its turn, to explore the Civil War, this

time through the lens of a camera.

With “Photography

and the American Civil War,” on view through September 2, 2013,

the Metropolitan Museum of Art explores the bloodiest war of American

history through the lens of a newborn medium, since the first photograph

of history was taken less than 50 years before the Civil War began.

The museum has

compiled more than 200 poignant photographs that capture the four-year

war from beginning to end. From Mathew B. Brady, known as the photographer

of the North, to George S. Cook, known as the one of the South, the

exhibition displays shots by four dozen of named photographs and countless

unknown artists. The beginning of

the war is illustrated with dozens of portraits of soldiers. The evolution

of the civil war seems to have followed the emergence of popular photography.

As the prices lowered and the quality rose, portraiture moved from a

luxury to a necessity, leading the combatants in uniform to pose for

carte-de-visite pictures. The exhibition displays dozens of these wallet-size

photos, both from North and South. It offers to put names to the faces

of the more than three million soldiers who fought during the Civil

War (Two million for the United States, one million for the Confederate

States). In the mean time,

world's first photographic campaign buttons were distributed to the

population. They were used by the four political parties (Republican,

Southern Democratic, Constitutional Union and Democratic parties) battling

out for the presidential election. Those buttons consisted of miniature

tintype images and displayed a tiny photograph of the candidate on one

side and an image of the vice-presidential candidate on the reverse.

One of the most

enthralling parts of the exhibition is the large collection of battlefield

snapshots, notably the one from Mathew B. Brady, who set up the first

gallery exhibition of Civil War photographs, “The Dead of Antietam,”

in 1862 in his New York City gallery. At this time, the New York Times

wrote: “In all the literal repulsiveness of nature, lie the naked

corpses of our dead soldiers side by side in the quiet impassiveness

of rest... The enterprise, the perseverance and courage, physical and

pecuniary, which suggest to and encourage an artist in such work as

this, establish for him forever a reputation such as no flattery, no

claptrap can secure.”

In reality, most

of Brady's photographs come from the photographers he employed, such

as Alexander Gardner, Timothy O'Sullivan or George N. Barnard. The result

is nonetheless appalling and the pictures of Antietam's battlefields

where dead bodies lie speak for themselves. The quality of the photographs

is also really impressive for the period, as seen in the exactness of

the lines and the accurate contrast of the colors. Pictures of the same

kind were taken during the Battle of Gettysburg (1863) which involved

some 160,000 soldiers for three days and marked the turning point of

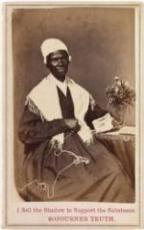

the Civil War. See below the stunning shots by Timothy O'Sullivan. During the four-year

“Freedom War,” as it was called by the Black southerners,

came the ratification of the thirteenth amendment that abolished slavery

in December 1865. Almost 200,000 African-Americans served in the Union

Army and both free and runaway slaves joined the fight. The exhibition

illustrates the first steps of those emancipated slaves, posing for

their first portraits. It also pays tribute to Sojourner Truth and her

iconic portrait entitled “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.”

An antislavery activist, she claimed to own her image, her “shadow,”

and therefore sold photographs of herself to raise money to educate

and support emancipated slaves.

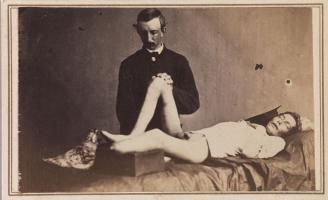

The part of the

exhibition dedicated to medical portraits of the wounded and sick will

send shivers down your spine. Taken by Dr. Reed Brockway Bontecou, the

album contains 570 medical teaching images. The pictures were shot when

soldiers arrived from the field, before and after the surgeries and

upon recovery. They still express today, 150 years later, an impressive

reality. A final room is dedicated to the end of the war and Lincoln's assassination. It is essentially organized as a memorial, featuring for instance the first photographically illustrated “Wanted” poster that led to the capture of Lincoln's murderer, John Wilkes Booth, and Alexander Gardner's exclusive views of the hanging of the conspirators.

If you go:

Adèle Bossard is a free lance writer from Saumur, France. |