Museums and Exhibitions in New York City and Vicinity

| Home | | Museum Guide | | International | | Architecture & Design | | Theater |

GLENN LONEY'S MUSEUM NOTES

CONTENTS, January 10, 2000

[01] The Great Orsay Clock

THE GREAT GOLDEN CLOCK OF THE MUSÉE D'ORSAY.

Photo: Copyright ©—Glenn Loney 2000/The Everett Collection.

[02] Where's the Train To Orléans?

[03] Stocking the Orsay Museum with a Little Bit of Everything

[04] Theo van Gogh as Art Dealer & Collector

[05] Fauvism at Paris MoMA—Trial by Fire

[06] Women Painters of the Académie Julian aat the Dahesh Museum

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

For editorial and commercial uses of the Glenn Loney INFOTOGRAPHY/ArtsArchive of international photo-images, contact THE EVERETT COLLECTION, 104 West 27th Street, NYC 10010. Phone: 212-255-8610/FAX: 212-255-8612.

Copyright © 1998 Glenn Loney.

For a collection of Glenn Loney's previous columns, click here.

EXPLORING PARIS MUSEUMS—

THE GREAT CLOCK OF THE MUSÉE D'ORSAY

No matter where a traveler was standing in the vast hall of the Gare d'Orsay, he had no excuse for missing a train because his watch was wrong—or had stopped. This magnificent gold-framed clock dominated the great glass-and-steel atrium of the most handsome railway station in Paris.Today, it remains the highly visible signature-image of the fin-de-siècle grandeur that made the Orsay Station admired all over Europe. And it reminds the hordes of visitors who throng the atrium—now reborn as a museum—when it's time for a lunch in the ornate Belle Époque restaurant which was once the sumptuous dining-room of the elegant hotel which fronted the actual station.

| |

| SEINE RIVER FACADE OF MUSÉE D'ORSAY. Photo courtesy of Musée d'Orsay. | |

If you are on one of those "Paris on $50 a Day" budgets—it used to be "$5 a Day"—and fear you dare not splurge on the delicious plats, entrées, et desserts of the grand restaurant, you can snack inexpensively inside one of these tower-clocks.

What's more, as the great minute-and-hour hands move inexorably, you can actually look out through the glass face of the clock and see the Louvre gleaming in the sun.

That is, if it's not raining, snowing, or blowing down the ancient trees along the Seine, as it did just before the memorable Paris Millennium Celebrations.

| |

| STUDYING VAN GOGH'S "WOMAN OF ARLES" IN THE MUSÉE D'ORSAY. Photo: Copyright ©—Glenn Loney 2000/The Everett Collection. | |

And there other earlier masters like Ingres, Millet, Bonheur, Delacroix, and Winterhalter—whose portrait of Mme. Rimsky-Korsakov is stunning.

Film and photography are also important at the Orsay, not least because some of the most significant experiments in cinema began in Paris with Georges Méliès and the Brothers Lumière.

And, while the Orsay pays visual tribute to Julia Cameron and Lewis Carroll, it gives pride of place to such noted French photographers as Atget and Nadar.

Paris is a city of high points, historically, architecturally, gastronomically, and culturally. But, because of its artistic inclusiveness, a day—or even several days—spent in the Musée d'Orsay can be the highest point of your next visit to the City of Light.

If you have never been to Paris, or to the Orsay, your appetite for a visit will certainly be whetted by studying a copy of "Your Visit To Orsay." It's available in major languages, just out this year.

In a large 9"x12" format, its splendid full-color reproductions work magically in evoking the artworks. Major works are shown in full in small photos, with full or double-page spreads of important details from the paintings, sculptures, or decorative arts.

Each has explanatory text, full catalogue listing, historical context, and a graphic indication of where to find the artwork in the museum.

I purchased this excellent guide on my way out. I thought it too heavy to carry around, but after looking at it back at my hotel, I was eager to return to the Orsay and look more closely at each work.

In fact, I almost missed that famous and formerly scandalous Manet painting of Olympia, as well as his equally infamous—but also oddly erotic—nude lady picnicking with two fully dressed gentlemen on the grass. The small crowded chambers don't give pictures like these the space they need.

At the rear of the great atrium—among some interesting but underlit architectural models—is a glittering and amazing reconstruction of the old Paris Opéra, Palais Garnier. This was constructed, from 1982-86, under the direction of Richard Peduzzi, who designed Patrice Chereau's memorable 1976 Bayreuth Centennial RING.

In longitudinal section, it shows in detail every aspect of foyer and auditorium decoration and stage-machinery. Nowhere is a Phantom of the Opera to be seen, but the model shows quite clearly that Garnier designed the major spaces of his opera as separate units with different roofs.

Vincent's Brother, Theo, as Dealer and Collector

| |

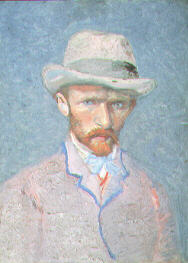

| VINCENT BY HIS OWN HAND. Photo: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation. | |

A family-tree with photos shows the Van Goghs to have been a handsome family indeed. Obviously, this unusual show helps fill in some of the blanks in the general account of Vincent's life—and especially his relationship with his very supportive brother.

But, for many admirers of Van Gogh's works, Brother Theo—if recognized at all—is that dedicated letter-writer who understood his brother's genius when Vincent himself doubted and the larger world ignored him.

So it is now really helpful to be able to see what Theo liked and collected himself, who his artist-friends and art-buying clients were, and what they liked and collected.

Among the canvases on view is one of those pre-Maxfield Parrish Neo-Classic fantasies, Fête Céréale, by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. This exotic exercise in mythology was on loan from the Forbes Magazine Collection on Lower Fifth Avenue.

[If Steve Forbes' presidential bid fails again this election-year, he could sell some of the paintings to the Orsay!]

| |

| EMILE BERNARD'S SELF-PORTRAIT, WITH PAUL GAUGUIN ON THE WALL. Photo: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. | |

Other paintings include works by Pissarro, Corot, Maris, Daubigny, Monet, Renoir, Toulouse Lautrec, and Emile Schuffenecker.

Some outstanding Gauguins are also in display. And, of course, some important Van Goghs. What Van Gogh is not important today?

I cannot find any note in the press-materials that this will travel to another museum. If it does not, that will be a great loss for many who are interested not only in Vincent Van Gogh's paintings, but also in his tormented life.

That's not the major purpose of this exhibition, obviously, but it certainly provides a meaty footnote to the Vincent Van Gogh Chronicle.

And it was time that Theo have some of the spotlight for himself. He was much, much more than a fraternal support-system for his far more famous brother.

| |

| MYTHOLOGICAL ART DECO RELIEFS ON PARIS MoMA. Photo: Copyright ©—Glenn Loney 2000/The Everett Collection. | |

This elegant Moderne Palace could have been a sister to some Art Deco structures at the San Francisco and New York World's Fairs in 1939. But those American Deco Pavilions were molded in lath and plaster. They were not destined for the Ages.

The Palais de Chaillot has similar Art Deco lines and sculptures and was also created for prewar fair. It is being renovated, as are a number of other Paris landmarks.

Finishing photography of the Deco reliefs brought me into the Fauvist exhibition via the bookstore. And past some homeless Parisians, sleeping on the steps of this ill-maintained courtyard.

Thus it was a great surprise, as I left by what I thought was the rear door, to find several hundred people in line there, in a light rain. Waiting for admission—which I had found immediately.

I showed my press-card to a lady at a table on the side—apparently she was dealing with groups—and she gave me a ticket. She also seemed glad to receive the brochures from MoMA and the Whitney in New York. I hope she was able to pass them on to the Press-Officer.

Parisian Salon Painting for Women at the Dahesh

| |

| PORTRAIT OF MLLE. BREUIL--In 1892, painter Rose-Marie Guillaume demonstrated skills mastered at the Académie Julian. Courtesy of Dahesh Museum & André Del Debbio Collection, Paris. | |

So it was now safe—indeed a good investment—for private collectors to purchase such paintings. And it often proved an investment in the future of their collections for museum curators to acquire such canvases.

But even artists of undoubted talent and skills were on occasion rejected. Edouard Manet is a notable example.

Unfortunately, talented women artists found it much more difficult to win Academy and Salon approval. The prestigious École des Beaux-Arts would not even accept them for training.

Rodolphe Julian, however, broke the rigid mold and encouraged women artists of ability to study at his Académie Julian. This was not for want of talented male students. Among those who studied there were Matisse and Vuillard, and even the Americans Robert Henri and John Singer Sargent.

Now, at the Dahesh Museum on Fifth Avenue in midtown, the works of some of the brilliant women who studied at the academy are on view. Germany's impassioned Expressionist Käthe Kollwitz was one of the graduates.

The show's title is: Overcoming All Obstacles: The Women of the Académie Julian. As the wall-texts and the show-catalogue amply illustrate, the obstacles weren't only encountered in trying to obtain good training. The Dahesh—which specializes in the kind of 19th century paintings so admired at the Salon—renders a unique service in making the names and works of the women on display better known. It should be of special interest to feminists who already know how difficult it has been for women artists over the centuries to make their marks. [Loney]

Copyright © Glenn Loney 2000. No re-publication or broadcast use without proper credit of authorship. Suggested credit line: "Glenn Loney, Curator's Choice." Reproduction rights please contact: jslaff@nymuseums.com.